Governance of salmon and people in Alaska has changed through the centuries. Indigenous groups exercised governance over salmon and people through concepts and practices developed through centuries of interaction, observation and use. Indigenous Alaskans operated on worldview beliefs substantially different from those of the European and Euroamerican populations who arrived in the 18th century.

Governance by Indigenous Groups

The worldview and practices of Indigenous Alaskans were built on three important principles. First, that all entities have spiritual essences (“persons”) that were fundamentally similar to those of humans and that those spiritual essences were attentive, sentient, volitional and required respectful treatment. Second, human beings had moral and existential obligations to maintain respectful relations with living and other entities on whom they depended in order for those forms to continue to give themselves to humans for the survival of both. Third, the spirits of living forms, including humans, upon death pass into another dimension and from there return to the living world through rebirth. This process is referred to as “cosmological cycling” and is dependent on human actions, ritual and otherwise, for the continuity of existence (Fienup-Riordan 1983:189). Human beliefs and behaviors were codified and passed on through mythic charters/covenants, spiritually informed ritual practices and liturgical forms that were handed down from generation to generation. While spiritually informed and motivated, Indigenous Alaskans closely observed salmon comings and goings, built complex understandings of salmon behavior, requirements, habitats and life cycles and mobilized the accumulated empirical knowledge to utilize and sustain salmon populations. They also created social systems limiting access and insuring nonwasteful use of salmon. Three examples of the governance of relations between people and salmon conducted by indigenous Alaskan groups are provided; other Indigenous Alaskans had systems of belief and practice similar to those described here.

–Tlingit–

The Tlingit are the indigenous occupants of the northwestern shores and islands of North America from the Bering River to Dixon Entrance. Southeastern Alaska is composed of the islands of the Alexander Archipelago and the coastal strip from shores to the crests of the Coastal Mountains. Due to the high rainfall characteristic of the region, there are 3,000 documented salmon spawning systems ranging in size from small rivulets to the large mainland rivers – Chilkat, Taku, Stikine, Unuk and Chickamin. All five species of salmon run in the larger mainland rivers but king salmon do not run in the smaller streams found in the islands.

Archaeological and linguistic evidence indicate that Tlingit ancestors were present from at least 6,000 years ago (Langdon 2014). Tlingit society was organized into approximately 15 sociogeographic units referred to as kwaans. Kwaans in turn were composed of core clans who owned lands and resource territories within the kwaan and co-occupied winter villages in the kwaans residing in substantial wood plank houses. Clans were organized into two divisions (moieties) – Raven and Eagle/Wolf – and social rules banned intermarriage within a clan or moiety so that persons were required to marry a person of a clan in the opposite moiety. This social and moral rule set in motion a series of exchanges between the clans that can be referred to as “obligatory reciprocity.”

Tlingit society had exceptionally strong property concepts. Clans were corporate units in that they owned both tangible and intangible property. Clan leaders (sha da hunee) were trustees who coordinated social relations, and were responsible for maintaining the corporate trust and passing it on to descendants. Special relations with places were memorialized in at.oow – objects, stories, dances, crests – that represented the clan history and claims to the location, territory or resource. Salmon stream ownership was one of the most important forms of property held by clans. Salmon streams were under the control of stream chiefs (heen saati) who exercised governance by determining who had access, harvest timing, technology and location of harvests. In general, other Tlingit respected clan claims to streams but if they were violated, Tlingit would use violence to protect their claims.

Salmon were the most important resource for the Tlingit. Tlingit relations with salmon combined spiritual understandings and perceptions with pragmatic empirical engagement, knowledge acquisition and practical intervention. The spiritual underpinnings of the Tlingit relation with salmon are conveyed in the mythic charter/covenant now referred to as the Salmon Boy story. According to the account, a young boy was taken by the Salmon People to their village underwater following his insult to a piece of dried salmon he was offered as food. The boy saw that under their skins, salmon were “people” and he was taught many things by the Salmon leader about how humans must treat salmon with respect in various ways so that salmon could return travel back from the ocean to their spawning streams. After several years, he returned with the Salmon people and was captured by his father. After his transformation back to human form, he told his family and relatives what he learned from the Salmon people about how they were to be treated so that they could return and be reborn. These teachings were passed down through the generations and as a charter/covenant provide the prisms through which Tlingit experience and relate to salmon and the prescriptions for how salmon are to be treated with respect.

Respect for salmon was shown by Tlingit in numerous ways including crying out a greeting to them as they jump out of the water approaching a stream, singing and dancing for them as they enter the streams, carefully handling them as they are harvested and processed, and releasing their spirit so it can return to their underwater home and be reborn (Langdon 2006b). In the realm of human social activities, salmon were honored as clan crest symbols, by creating beautiful images of them on blankets, hats, boxes, screens and totem poles and by giving humans names based on salmon characteristics. They were to be spoken of and to with respect and never insulted or abused.

Archaeological evidence shows that Tlingit began building intertidal fishing structures to capture salmon over 5000 years ago (Smith 2011). This evidence is most abundant in southern southeast Alaska where remains of intertidal fishing structures are found at the mouths of many streams peaking in abundance around 2000 years ago (Smith 2011). Approximately 1000 years ago, the Tlingit developed a an intertidal salmon fishing technology of semi-circular tidal traps that allowed salmon to ascend to their spawning grounds on each high tide and only captured those that backed out on the ebb tide (Langdon 2006a). This innovation is termed “tidal pulse fishing” (Langdon 2006a)

A number of governance practices were developed by the Tlingit to sustain salmon. Informed by the Salmon Boy account, Tlingit developed the concept of ish, a deep hole in a stream where salmon congregate to rest as they proceed up a stream to their spawning grounds. The ish was used as an index of return adequacy – the heen sati required that it be filled with salmon before harvests would be allowed below the ish in the intertidal area or in the stream (Langdon 2006b). Tlingit were enjoined to take only what they needed, to not waste any portion of the salmon, and to store them safely so they would not spoil (Langdon 2006b).

The Tlingit harvested selectively by sex. They took mostly males, in a ratio of 3 to 1 (Langdon 2006b). The heen sati monitored the stream and removed fallen rock, excess brush or tree debris that blocked the upstream movement of salmon. When beaver dams blocked sockeye salmon access to their spawning locations, the heen sati had the dams taken out (Langdon 2006b). Tlingit viewed Dolly Varden and certain birds as endangering salmon egg deposition and outmigration and limited their numbers to control excessive depredations on young salmon. In streams where salmon runs had decreased or had been blocked for some time by slides, Tlingit transplanted salmon in various ways to replenish the streams (Langdon 2006b). This was done by bringing male and female salmon from other stream systems and releasing them at the stream mouth or in the case of sockeye at the lake outlet (Langdon 2006b). In at least one case, this procedure was used in an attempt to establish a late chum run in a system in order for the clan to have access to salmon later in the year when they had time to process them (Deur and Thornton 2015).

The governance system of salmon engagement developed by the Tlingit was successful in sustaining highly productive systems for thousands of years. The system can be characterized by the term “relational sustainability” – through spiritually inspired prescriptions and actions Tlingit sought to maintain existence, as they knew it.

–Ahtna–

The Ahtna live in the Copper River valley above Miles Lake to its headwaters and in the upper Susitna valley to the west. The Copper River has numerous tributaries that support runs of king, sockeye and silver salmon including the Chitina, Tonsina, Tazlina, Klutina, Gulkana, Slana, Mentasta and Tanada. Ahtna utilized all of these rivers to acquire salmon. Salmon were the primary food resource utilized by the Ahtna who processed thousands of fish in the summer for food in the winter.

Ahtna have been present in the Copper River valley for about 5000 years (Potter 2008). Most Ahtna followed an annual cycle in which they lived in villages near the Copper River in summer where they put up salmon, traveled up the river valleys to hunt caribou, moose and sheep in the fall and returned to their villages with their harvests for the winter months. Ahtna society consisted of lower, middle, upper and interior or western divisions. The first three reference their position in the Copper River while the latter division occupied lands in the upper Susitna River valley. Ahtna were born into one of eight matrilineal clans that were positioned in two moieties – Raven and Seagull. Individuals were required to marry a person from another clan and moiety. Long-term interclan marital ties were characteristic as they established and maintained critical relations necessary for the conduct of potlatch ceremonies, key events in sustaining the continuity and governance of Ahtna society. Social units, called tribes or bands consisted of intermarrying members of clans and a primary clan was considered the owner of the territory. Early American explorers and prospectors in the region observed that tribal territory and boundaries were well-known and other tribes could not enter without permission or invitation for “if they did, it mean war” (Simeone 2018:31).

Contemporary leader Wilson Justin views clan territories as multidimensional spaces consisting of people, animals, plants, earth, water, and air – it is a landscape lived in and where “exclusive use and jurisdiction [has been exercised] over many, many, many, thousands of years” (Simeone 2018: 31). Governance of Ahtna society was conducted through the authority of denae and kaskae. Denae were clan headmen who were the highest-ranking person of the local clan and presided over the larger villages. Denae controlled distinct territories and made decisions about use of an area and its resources (Simeone 2018: 101). Kaskae were below the denae and presided over smaller villages. There were seventeen Ahtna denae with titles designating the locations of their jurisdiction (Simeone 2018: 100).

Ahtna viewed animals and fish as spiritual forms who gave themselves to humans, were controlled by powerful spiritual beings and with whom relations were governed by an elaborate system of rules and proscriptions called ‘engii a term that is synonymous with power (Simeone et al 2007:83). Mythic charters established compacts specifying how the reciprocal relationship between animals and human was to be conducted and authorizing certain forms of human use subject to conditions of appropriate action. The ‘engii for salmon was codified in an account of a young boy, Bac’its’aadi, who disappears from a salmon cache and later returns in the river the next year as a small king salmon. When he is taken by his relatives, the “boy …tells them the story about living with the fish and what they don’t like and what they do like” (Simeone 2018: 74). His teachings are the foundation for the salmon ‘engii that emphasize respectful treatment as the basis for the return of salmon “only to those who work on them carefully” (Simeone 2018: 75).

Governance of the relationship between people and salmon depended on teaching young people how to think and behave in order to sustain. Young people were taught the mythic charters and their significance, were required to observe and learn how to behave in general and in regard to salmon specifically, what were the appropriate behaviors that must be carried out to show respect to salmon. Particularly significant were learning the crucial behaviors, welcoming songs and dances that were to be conducted on the arrival of the salmon each year (Justin 2018 pc). Successful engagement with salmon required that all Ahtna participants must act in appropriate ways. Elders observed the behaviors of young people and only when they had demonstrated a full comprehension of the teachings and conducted themselves in appropriate ways without guidance were they considered “citizens”, meaningfully empowered members of the clan able and required to fully participate (Justin pc 2017).

Ahtna governance of salmon and relations with salmon involve a number of elements. Constant acquisition of observations about salmon and environment was ongoing and the information passed on was shared and recorded in detailed accounts of long-term changes to salmon runs found in Ahtna oral traditions (Simeone and McCall 2007). Ahtna understood the salmon life cycle as they observed it and had seven terms for different stages from eggs in redds to spawning stage and death (Simeone 2018: 75). Terminologies identified all five species of salmon as well as varieties of species, such as the large sockeye originally returning to Tanada Creek and harvested at Natelde (also known as Batzulnetas) an important fishing site in the upper Ahtna territory.

Most of Ahtna salmon harvests took place on the Copper River proper from the shore or fishing platforms using dipnets (Simeone 2018: 57). Only a few locations in the smaller shallower tributaries in the northern area were suitable for weirs and basket traps. Ahtna throughout the Copper River preferred males over females because they were “larger and fatter” (Simeone and Kari 2002: 168). Of the 88 documented traditional Ahtna salmon fishing locations in the Copper River system, 17 of them belonged to specific denae (Simeone 2018).

Approximately a month before the expected arrival of salmon at Batzulnetas, men of the local group would travel the course of Tanada Creek and tributaries to Tanada Lake where sockeye were known to spawn and remove any beaver dams they found (Justin PC 2018). At Batzulnetas, the spiritual welcoming of the return of the salmon would be undertaken as a moral obligation conducted by the kaskae. During the period of waiting for the arrival of salmon, loud noises were prohibited, speaking softly was required, no entry into water was allowed, people moved slowly and with limited motion, and rounds of sweat bath cleansing and purification were undertaken (Justin 2017 pc). Ahtna believed that “salmon return to their natal streams to give themselves for harvest…If the fish are not used they will not return to their natal streams” (Simeone and McCall 2007: 40).

When the first salmon appeared, the people wore special clothing as they performed welcoming songs and dances that were to be conducted on the arrival of the salmon each year (Justin 2018 pc). Following these ceremonies, the conduct of salmon harvest was placed under the direction of a “salmon boss” would be given the authority and responsibility by the denae to ensure social obligations were met and that all eligible fishing parties had a spot. Harvest supervision included timing on placement of the weir, overseeing the basket traps to insure they were emptied and that no wastage occurred, monitoring harvest levels and deciding when to open the weir to allow the salmon to ascend to the lake (Simeone 2018:109). Ahtna were enjoined to take only what was necessary and had target goals, measured in bales of fish that were adjusted based on need and environmental conditions (Simeone and Kari 2002: 169). Ahtna salmon governance was designed to serve the entire tribe through providing access, sharing, exchanging and bartering and to seek equity by avoiding greed and hoarding (Justin pc 2018).

The denae periodically decided that certain streams should or should not be fished in a given season. This was done because the run was limited and could not support a family, the previous cycle run had been very low or environmental factors were not favorable (Justin pc 2018). For example, there was a small stream with a limited king salmon run on the east side of the Copper River above Chistochina that people were rarely allowed to obtain fish from unless authorized.

Ahtna governance of salmon and people through spiritual obligations, empirically grounded observations and highly developed controls over fishing sites and fishing practices under the leadership of well-respected leaders was successful in sustaining the salmon runs and their use by Ahtna people for thousands of years.

–Central Yup’ik–

The Central Yup’ik were the most numerous of Indigenous Alaskans at the time of contact (Langdon 2014). They occupied the region from the Nushagak River in Bristol Bay north and west to the coast of Norton Sound. In addition, Central Yup’ik populations were established in villages over 100 miles up the Kuskokwim and Yukon River. For Central Yup’ik located on the primary rivers of the region – Nushgak, Togiak, Kanektok, Kuskokwim and Yukon – salmon were the primary resources. In Bristol Bay, sockeye salmon were the most important species while on the Kuskokwim and Yukon, king, dog, and to a lesser extent silver salmon were the most important. Marine mammals on the coast and terrestrial mammals upriver were significant additional resources where they were available.

Limited archeological evidence from the region indicates that Central Yup’ik populations are likely to have been present in the coastal area of the region about 4000 years ago gradually expanding south and east up the main rivers and into Bristol Bay (Van Stone 1967). Central Yup’ik society was organized on a village and local group basis with approximately 14 local group units identified by the suffix miut (“people of”) being found in the region. Each local group consisted of several intermarrying and ceremoniously interacting villages; typically, a pair of villages participated in reciprocal hosting of ceremonies at which the other village would be the invited guests. Local groups and their component villages had well-established territories for fishing, hunting, and gathering activities. Boundaries of the local group territories were well known, respected and protected. Extended intermarrying families owned fishing sites and camps where they went each summer to catch and process salmon, returning in the fall with their production to their villages. Salmon fishing was done primarily by set nets, dip nets and traps. Each village had a ceremonial or men’s house, known as qasigiq, where the adult men lived while their wives and children had smaller separate dwellings that the husband visited. In this ceremonial space, the Central Yup’ik conducted a range of social and spiritual ceremonies that were the lubricant and glue facilitating relations between humans and between humans and the spiritual world (Fienup-Riordan 1983, Meade and Fienup-Riordan 1996).

Central Yup’ik believe that all living and other forms had spirits that were sentient, attentive, communicative and volitional. A central concept in organizing their understanding of existence is Ella (Kawagly 1995:15) or Ellampiim yua – translated as “Spirit of the Universe”. This concept conveyed the essential quality of awareness and the preferred state of harmony in the universe. The spiritual heads of fish and animal species determined how the individual members of species would distribute or give themselves to different human populations depending on how they were treated. Salmon fell under this general framework of how species were to be treated. Central Yup’ik spiritual ceremonies were conducted under the direction of the angalquk (shaman) who had powers to communicate with spiritual forces of the fish and animals in the land of the dead. He designed and constructed masks based on his spiritual visions that he or others wore during the songs and dances the people performed during the “Season of the Drum” when many ceremonies occurred. Masks typically represented Ella as an oval form inside or around which were attached small images of fish and animals (Fienup-Riordan 1996). The masks were worn and performed during the dances and songs that were collectively conducted by the people of the community. The ceremonies were intended to honor and demonstrate interest to the spirits of the fish and animals “to insure the presence [and return] of the … animals that the people needed for survival” (Meade and Fienup-Riordan 1996: 25). These activities were referred to as agayu or “our way of making prayer” (Fienup-Riordan 1996, Meade and Fienup-Riordan 1996). Central Yup’ik elders referred to the purposes of these prayers as “clearing the path” for the fish and animals to return (Meade and Fienup-Riordan 1996: 29). Central Yup’ik believed that fish and animals presented themselves to people to be harvested and further that it was their moral obligation to take those that presented themselves (Fienup-Riordan 1990). To not do so would be taken as an insult by fish and animals who then would not return to those unwilling to harvest (Fienup-Riordan 1990). Further, fish were observant and attendant to the capabilities of Central Yup’ik harvesters’ abilities to provide respectful, clean, safe conditions for their processing and storage. These principles were taught to boys and girls with the admonition that failure to uphold them would result in the salmon not return to give themselves to the people and the people would starve. Respectful taking was fundamental to spiritual relationship between humans and other species.

For Central Yup’ik, the continuity of relations between themselves and salmon and respectful adherence to moral obligations they regarded as essential to their survival were collective responsibilities (Kawagley 1995). Through these spiritual beliefs, ceremonial actions and practices of careful, respectful use, the Central Yup’ik maintained relationships with salmon over thousands of years.

Governance during the Russian Period: 1741 – 1867

Europeans and Euroamericans brought with them a worldview grounded in the Biblical account of existence with humans as the chosen life form “made in the image of God” endowed by the creator with a spirit (soul) that would pass on to another existence and not return to this world. Further, other living forms did not have spirits like human souls and were to be used by human beings for their purposes. No relationship of a spiritual nature is posited in the Biblical worldview between humans and other living entities. The Biblical worldview is linear – life begins at birth, proceeds on a trajectory of existence, and ends with death. There is no spirit of the life form that will return to earthly existence through rebirth. The presence of fish and animal populations does not depend on relations with those organisms in the Biblical worldview.

From 1728 to 1741, Russian explorers landed on the shores of Alaskan islands in the Bering Sea and the Gulf of Alaska. These voyages were authorized and underwritten by the Russian government with the intent of establishing a claim through the European doctrine of discovery (Black 2004). In 1741, the vessels of Vitus Bering and Alexei Chirikov encountered indigenous groups in southeast Alaska and in the Shumagin Islands. In addition, on Kayak Island near Prince William Sound, the Russian naturalist Georg Steller discovered “pure and well prepared”… “smoked sockeye salmon in baskets” in an unoccupied Chugach Alutiiq barabara noting that “based on taste… it was superior to that of Kamchatka” (Grinev 2013: 8). Information on the abundance and availability of sea otters in the Aleutian Islands brought back by the explorers prompted Russian companies to support the movement of crews of hunters (promyshlenniki) into the islands to obtain the animals (Black 2004). With the claim of discovery established, the Russian government “left [it] to the private entrepreneurs to validate this claim by the right of occupancy” (Black 2004: 39).

Russian governance was limited to the geographic areas where they were able to establish control over the indigenous populations. By the 1770s, control was established over the Aleut communities, by the 1780s over the Koniag and Chugach Alutiiq and by the 1790s, some control over the eastern region of Bristol Bay as well. In Cook Inlet, Russian control extended only up to the area of Kenai. In these areas some forms of Russian governance was exercised over the indigenous people, the salmon resource and the use of the salmon resource. In southeast Alaska, Russian control was limited to Sitka and for a short period Yakutat. Elsewhere in Alaska, indigenous groups either traded with Russians thereby maintaining their governance over the salmon resources and their labor or were not in direct contact with Russians.

Governance of salmon and people during the Russian period changed over time. Following their arrival, Russians observed and reported on salmon in abundance and the Aleuts use of them on Unalaska Island and Alutiiqs on Kodiak Island. While the early Russians “caught fish themselves…more often [they] acquired them from the local residents” (Grinev 2013:5). Thus the governance of the resource, the mobilization of labor for harvesting and processing, and the technologies of procurement remained under indigenous control. Sometimes Russians were given fresh or dried salmon but more commonly, a trade relationship was established whereby the Aleuts and Alutiiq supplied salmon (and other fish) in exchange for trade items such as tobacco, beads, copper kettles and other goods. In some cases, Russian took salmon from the indigenous groups by force (Grinev 2013:15).

Other European explorers also began appearing on Alaskan shores in the late 1700s notably the Spanish (1775-1792), the British (1778-1794), and French (1786) where they encountered indigenous groups using salmon. During their earliest encounter with Tlingit north of Sitka in 1775, the Spanish discovered that Tlingit exercised strong territorial rights and objected to the Spanish attempt to take freshwater from the stream in front of the Tlingit fish camp. In 1779 in Bucareli Bay on Prince of Wales Island, Spanish explorers found indigenous groups catching king salmon trolling and set up a market on shore near their anchored vessels where they traded iron and other items for salmon and halibut from the Tlingit and Haida (Langdon 1997). In 1778, Captain Cook’s crew caught their own salmon with a seine while at Unalaska. In 1786, the party of the French explorer La Perouse discovered Tlingit groups capturing salmon with fish traps in Lituya Bay. Upon request by the French to obtain some salmon, the Tlingit allowed the French to take a substantial number from the traps for their own use – no information was given on whether Tlingit required payment of some kind for this allowance. In these accounts, where indigenous groups are encountered by explorers, indigenous governance over the resource, its harvest and distribution was maintained.

Russian settlements expanded in the 1770s and 1780s to the Kodiak Archipelago, Cook Inlet and Prince William Sound. Russian settlements were dependent on salmon as the mainstay of their winter food supply and thus were often established at the mouths of productive systems. During this period, large numbers of Aleut and Alutiiq men were forced into long expeditions to hunt sea otter at locations far distant from their home communities. Their absence for long periods placed great stress on those left behind to obtain the necessary salmon and other fish for winter food stores and they frequently were forced to eat wood bark, shells or dead whales to avoid starvation (Grinev 2013: 14).

In addition, Russian methods of acquiring salmon shifted from trade to appropriation as they captured Aleuts, especially women and children, to work on salmon processing. The Russians utilized slaves taken from the Aleut and Koniag and kaiury (conscripted labor) to work on salmon acquisition and processing (Grinev 2013). The period from the 1780s to the 1820s was the most severe as indigenous governance of salmon in those areas controlled by Russians was displaced as much of the production of salmon went to provisioning the sea otter hunting crews. Working substantial amounts of time for Russian overlords likely limited indigenous group’s ability to put up their own stores. When food shortages occurred in winter, Russian reports state that in certain areas indigenous residents would come to the Russian outposts requesting food which the Russians supplied (Grinev 2013).

Reports about the mistreatment and abuse of indigenous people were received by the Russian explorer Billings in 1799 who informed the Russian court about these conditions. The Russian court directed that no further forced labor was to be used and that indigenous fishermen were to be paid for their efforts. Russian records report salmon harvests in units of yukola (dried salmon) for a number of locations at various times during their jurisdiction. Locations in the Kodiak Archipelago appeared to have been a primary source during the 1820s when demand was at its peak. Russians discovered the enormous productivity of the Karluk system and began taken substantial quantities of salmon from that location (Roppel 1986). One Russian observer estimated that as many as 10,000,000 salmon returned annually to the Karluk system (Grinev 2013: 2). Salmon from Karluk and elsewhere not only fueled the indigenous sea otter hunters but also provisioned other settlements as well (Grinev 2013). Russian reports identify the following as quantities taken from Kodiak salmon systems in the 1820s (Grinev 2013: 15):

- Karluk – 300,000

- Three Saints Bay – 90,000

- Buskin River – 80,000

- Alitak – 70,000

- Igak artel – 60,000

- Afognak – 15,000

All of this salmon production was used “exclusively for internal consumption and was distributed, not sold, on the basis of the current needs of specific settlements and artels for food for Russians and Natives” (Grinev 2013: 15).

The fortunes of the Russian American Company turned south in the late 1820s due to decline of sea otter populations resulting from extreme over-harvesting. The Russians implemented sea otter conservation measures limiting areas and quantities to be harvested that resulted by the 1860s in a significant increase in the population.

Four other locations were sites of substantial Russian focus on salmon production, two in Cook Inlet and two in southeast Alaska. The Russians established outposts on the Kasilof and Kenai Rivers in Cook Inlet both of which support substantial multi-species salmon runs. In both locations indigenous populations were conscripted and hired as the work force for salmon production effectively displacing indigenous governance and replacing it with Russian control. In 1860, Russian sources reported putting up 9000-10,000 dried fish from the Kenai River for local consumption primarily by hunters (Grinev 2013: 34).

Russian sources report that trading posts established on the Yukon and Kuskokwim after 1800 acquired dried salmon by purchase from local indigenous populations (Grinev 2013).

In southeast Alaska, Russians established settlements at Yakutat and Sitka but had no control (governance) anywhere else in southeast Alaska. At both locations, salmon production was an important feature of Russian occupation and their methods of governance precipitated major instances of violence (Grinev 2013). At Yakutat, the Russians were allowed to establish a settlement by one segment of the community inn1796. They then took charge of major salmon fisheries used by the Tlingit without their concurrence. Russians blocked access of the Tlingit to their fishing sites causing great shortages. In 1805, in response to these denials of access and other depredations, the Tlingit killed the Russians thus ending their occupation of the site.

The Russians obtained Tlingit agreement to establish a trading post at Sitka in 1799. In 1802, the Tlingit destroyed the outpost due to Russian depredations and invasion of the Tlingit sea otter hunting grounds. Just south of Sitka is a moderately sized sockeye salmon system now called Redoubt. Upon their return to Sitka in 1804 and re-establishment of their settlement, the Russians established a fishery at this site referred to as Ozerskoi Redoubt. One Russian source indicated that the Tlingit owner of the site was recognized and given blankets for use of the site. However, Tlingits were not allowed to return to Ozerskoi for their own harvests. From 1805 to 1830, Russian annual harvests of salmon from Ozerskoi fluctuated between 50,000 salmon (predominately sockeye) and 80,000 (Grinev 2013: 22). By the 1850s, Tlingit resentment of the Russian usurpation of their most important salmon harvesting site grew to the point of violence. In 1851, Tlingit attacked the Redoubt and the Russian fishermen at Ozerskoi on several occasion halting their fishing and taking their production. In other nearby areas where the Russians attempted to fish, Tlingit obstructed and halted Russian fishing efforts (Grinev 2013:20). Tlingit did not accept Russian governance of their traditional salmon fisheries in the Sitka vicinity and resisted them with the intention of returning those fisheries to Tlingit governance.

The Russians often were not able to produce enough for their own food requirements at Sitka. A market for food sales was established next to the fort where Tlingit sold their food production to Russian residents at rates established by the Russian American Company. In the summer and fall, Russians bought hundreds of fresh salmon from the Tlingit, mostly for the consumption of company administrators (Grinev 2013: 21). Outside of Sitka and the Ozerskoi fishery, Tlingit governance of territory and their salmon fisheries remained in place as the mechanisms for provisioning the Russians who came to heavily depend on the Tlingit for food (Gibson 1987).

By the mid-1840s, the Russian American Company was in desperate circumstances. In order to address revenue shortfalls, a new trading initiative was explored with salmon, ice, wood products and fur seals as the principal assets to be sent from Russian America. In the late 1840s, trade with Hawaii was slightly successful but only small quantities of salmon were exported. The trade declined due to competition from the British who provided cheaper and better products from British Columbia. In the mid-1850s, a new agreement with a San Francisco firms led to export of Alaskan ice, lumber, coal and salted salmon. By the end of the 1850s, the salmon trade to California ended due to poor salmon salting, product spoilage from a lack of quality barrels and inability to compete with much less expensive local products. A final attempt in the mid-1860s to export salmon strained the fishery at Ozerskoi as the harvest nearly doubled from previous high to almost 150,000 salmon (Grinev 2013). In the 1863, the Russian American Company reported that at Ozerskoi, the “fish run was not very abundant” (Grinev 2013). This final push for profitable export likely led to overharvesting salmon at Ozerskoi and to declines that persisted at the site after the coming of the Americans.

Despite these setbacks in producing salmon for trade export, a number of Russian American Company personnel in the 1850s and 1860s believed that fisheries “would be the most important futures source of wealth for Russian America” projecting future profits of $40-50,000 annually (Grinev 2013:26). They developed proposals for expansion of the fisheries but noted that the company must shift efforts from fur acquisition to preparation of fish if the benefits were to be realized (Grinev 2013: 26). The company directors, however, were not convinced. In 1862, based on failures of the earlier Hawaii and California initiatives due to high expenses in production and transportation the company concluded that “substantial permanent fish trade is positively impossible” (Grinev 2013: 26).

While indigenous governance of salmon had been overcome or challenged by the Russians in some areas, the majority of Indigenous Alaskans continued with their systems of salmon governance intact at the end of the Russian period. Noteworthy, however, was that smallpox epidemics in the 1830s and 1860s as well as other diseases such as measles, flu, had devastated the overall populations of Indigenous Alaskans and related ailments not previously found in Alaska. In addition, the depredations of Russian rule during the early period of occupations was a major factor in reducing Aleut and Koniag population numbers. Aleut populations declined by 80-90% by the mid-1800s forcing massive population movements and settlement consolidation directed by the Russians. In other parts of southern Alaska, it is estimated that populations declined by 50-75%.

In 1860 it was reported in company documents that the total amount of Alaska salmon taken was 550,000 only a fraction of which were exported for sale. Nevertheless, Russian sources provided justifications to the American representatives that the region’s fish resources would become a source of great wealth. American politicians supportive of the purchase of Alaska were quick to accept these views – for example Senator Sumner and Secretary Seward – and use them to bolster their arguments for acquisition.

Governance during the US Federal period: 1867-1959

When the US assumed jurisdiction over Alaska following the Treaty of Cession with Russia in 1867, the governance of salmon and those using them was under the control of Indigenous Alaskans as it had been in most places for thousands of years. Despite substantial population declines resulting from the spread of epidemics from smallpox (1830s and 1860s) and other introduced diseases, indigenous Alaskan populations maintained their communities and depended on local resources for survival. Salmon were the most important staple food for Indigenous Alaskans in virtually all areas where they were present in substantial numbers and their harvest and processing for winter consumption was the focus of intense efforts in the summer and fall.

The legal doctrines of the United States regarding fisheries is that in the ocean they were “common property” available to all and that fish only became property after they were taken into possession or captured in some kind of fishery. Salmon presented a complex situation as they were found both in the ocean and in inland streams. The harvesting of salmon on rivers and streams were a condition of access i.e. property owners controlled access to the streams that bordered their land but the general public presumably could access salmon on streams running through those lands. Federal laws and regulations, however, could limit passage across or the taking of salmon from those waters.

Federal mixed governance: 1867-1884

Alaska was placed under the authority of the War Department and assigned to the Army during the first ten years of US rule. The Army operated under the principles of the Indian Intercourse Act of 1934 that limited them to basically maintaining peace and recognizing Indian governance and resource uses although following a court decision in 1872, only the provisions of the act banning the import and sale of liquor could legally be enforced in Alaska (Haycox 2002). With the Russians gone, indigenous populations throughout the state resumed governance of salmon fisheries that had previously been appropriated from them. In his departing address upon leaving his command Alaska’s first federal authority, General Jefferson Davis, presciently predicted that conflicts over salmon would soon arise between Alaska Natives and non-Native newcomers and that the government should take steps to resolve the looming crisis.

In 1867, there was only one commercial salmon operation for export in Alaska – this was the saltery operation of Count Baronovich, an Austrian nobleman from Victoria, at Kasaan on the east side of Prince of Wales Island (Tidball 1870: 84). The Karta River that was the source of the salmon used for this operation was owned by Haida leader Skowl whose daughter was married to Baronovich. Skowl’s extended family harvested the sockeye salmon and salted it in barrels for export to Victoria. According to Tidball, the Indians “acquired the salmon by their own methods” (Tidball 1870:84). In 1875, the ethnological collector James Swan visited Kasaan and was taken to the Karta River fishing grounds where he observed the indigenous fish traps. He sketched their position in the river showing that the traps covered only 50% of the stream (Langdon 2009).

On the west coast of Prince of Wales Island at Klawock, George Hamilton, a Scottish trader with ties to the Haida, established a saltery and trading post in 1870 authorized by the local Tlingit leader. Hamilton recognized the ownership of the Klawock River by the local Tlingit leader and utilized local Tlingit and Haida labor in his operations. Tidball reported that Hamilton exported 300 barrels of salted salmon 1870, the first year of operation (Tidball 1870: 85).

The new salmon canning process first utilized in Oregon in 1864 made its appearance in 1878 in Klawock where a firm of investors from San Francisco purchased George Hamilton’s saltery and trading post. They affirmed the recognition of the Tlingit leader to ownership of the Klawock River, paid him a lease and hired local Tlingit and Haida to work in the cannery (Moser 1899). The lease was recorded in the US Commissioner’s records at Wrangell in 1894. The auspicious relationship established at Klawock between the cannery personnel, the Tlingit owner, and the local indigenous residents continued for nearly 20 years (Moser 1899). Unfortunately, this pattern was not followed in most other Alaskan salmon sites. The profit realized by the Klawock cannery in its first year of operation paid for all of its initial costs and other cannery operations quickly appeared in southeast Alaska in the next few years (Langdon 1977). However, the relationship between the Tlingit and the cannery operators at Klawock was not without difficulties; as predicted by General Davis, troubles developed in a number of other places in southeast Alaska including Sitka, Sitkoh Bay, Chilkat, and western Icy Straits where Tlingits protested against canners using Euroamerican fishermen to harvest salmon from streams Tlingit claimed ownership of.

During the 1880s, the canned salmon industry spread rapidly across southern Alaska with new facilities appearing at the mouth of the Copper River, at Kenai in Cook Inlet, at Karluk on Kodiak Island and late in the decade in Bristol Bay on the Nushagak and Naknek Rivers. At these locations, American industrialists built their facilities and began harvesting and processing salmon with little to no regard for local populations. At Karluk, six canneries were built on the spit at the mouth of the river between 1882 and 1896 resulting in enormous competition and rapid depletion of the runs (Roppel 1986). Cannery fishermen threatened local Alutiiq with violence and prevented them from fishing (Arnold 1976). Cannery fishermen removed the boulders from the rocky beaches to make create a cleared space for their beach seines and then claimed ownership of those beaches denying Karluk natives and other non-Natives use of the cleared beaches (Grantham 2011). In many places in Alaska, completely dependent Chinese crews were imported as primary laborers in the canneries and segregated living quarters were built with separate facilities for whites, Natives and Chinese employees (Friday 1994).

Territorial Governance I: 1884-1912

In 1884 through the first Organic Act, civilian government was created in Alaska and an appointed Governor became agent of federal governance. There were no laws governing salmon fishing or processing for most of 1880s.

Fisheries science as a discipline was not yet in existence when the US acquired Alaska and little information on salmon as a species was available. The US Commission of Fish and Fisheries was created in 1871 with the charge to determine the causes of the declines in the fisheries and identify means to restore abundance. In 1881, agent Tarleton Bean visited Kodiak initiating federal research on Alaska salmon and fisheries (Gard and Borotoff 2014: 360). Federal officials received reports of massive harvests of salmon at Karluk in 1886 and 1887 (Roppel 1986). With mounting evidence of the destructiveness of early commercial harvesting activities, the federal government promulgated the first Alaska salmon fisheries regulation in 1889 (Roppel 1986). The law prohibited “the erection of dams, barricades or other obstructions in any of the rivers of Alaska.” While aimed at halting the barricading of streams at their mouths by cannery operators that prevented upstream movement of salmon, the law also effectively outlawed in-stream weirs and traps commonly used by Alaska Natives. It was not until 1892, however, that a “Special Agent for the Protection of the Salmon Fisheries of Alaska” was stationed in Sitka. As late at 1905, there were only three enforcement officers for all of the southeast Alaska and they were dependent on private parties (cannery vessels, Alaska Natives) for transportation to conduct their activities (Arnold 2008: 82). The legislation was amended in 1896, requiring that all salmon harvesting occur below the high tide level of any stream less than 500 yards in width at the mouth of the stream, a further blow to certain Alaska Native fisheries that had been customarily operated in intertidal waters.

Federal legislation in 1891 allowed the privatization of lands in Alaska for town sites and for up to 80 acres for sawmills and canneries. As result of this law, canneries were able to obtain title to lands at the mouths of the streams where they obtained salmon. Through such land acquisitions, Alaska Natives were displaced from a number of their traditional sites that were acquired by cannery owners.

An alternative form of development related to indigenous rights occurred in 1889 when the US government established a reservation for the Tsimshian Indians who had migrated to island across the border from British Columbia, with federal authorization in 1887. In 1916, the Annette Island Fisheries Reserve was created extending the reservation to 3000 feet offshore. The Tsimshians constructed floating fish traps and operated a successful, profitable cannery with virtually all indigenous labor for many years.

Jefferson Moser, another early federal fisheries researcher, documented salmon fisheries, harvesting and processing activities in the late 1890s (Moser 1899). He observed that at a number of locations in southeast Alaska, non-Native cannery fishermen blockaded streams and prevented salmon from ascending and reaching their spawning grounds (Moser 1899). He observed that the “laws and regulations pertaining to Alaska salmon fisheries are very generally disregarded, and that they do not prevent the illegal capture of fish” (Moser 1899:89)

Indigenous Alaskans in a number of places objected strenuously to Moser and other federal agents who occasionally appeared about the destructiveness of the methods used by commercial harvesters. Moser (1899:43) stated that wherever he anchored during his investigations of southeast Alaska salmon fisheries, Native leaders came to him and reported that the practices of the cannerymen in blocking the streams and making enormous harvests were destroying the resource and driving them to starvation. Moser (1899:43) was of the opinion, perhaps influenced by what he observed and learned at Klawock, that Alaska Native ownership of salmon streams should be recognized.

By the 1890s, cannery operators became concerned that salmon runs were declining and began contemplating artificial propagation. The first hatchery appeared at the mouth of the Karluk River in 1891 (Roppel 1982: 99). Hatcheries were seen by cannery operators as a way to replace wild stocks that were assumed to be disappearing and also as potentially producing even larger returns (Roppel 1982: 124). Many canneries followed suit and in fact, federal legislation was passed in 1900 requiring canneries to establish hatcheries to replace the number of fish used for their pack (Roppel 1982:153). Very few complied and the requirement was generally ignored by fisheries agents. Over the period between 1906-1915, the Bureau of Fisheries expended nearly $800,000 on the support of hatcheries and less than $150,000 on regulation and scientific research (Arnold 2008:86).

The Klondike gold rush that began in 1896 brought a surge of immigration to Alaska and led to an increase in the resident population (Haycox 2012). Many of those who did not strike it rich however remained in Alaska and sought employment in the salmon fisheries. Those who took up residency quickly adopted Alaskan identities. They joined Alaskan residents who as early as 1891 had organized in Sitka and sent a delegate to Washington, DC voicing a desire for greater Alaskan self-governance and indicating their dissatisfaction at federal control (Haycox 2002: 214). In 1906, in response to this growing cry, Congress authorized the election of an Alaskan delegate to Congress, a position filled over the years by many strong advocates for Alaskan self-governance and for consideration of the unaddressed rights of Indigenous Alaskans.

Rapid technological change in the harvesting and processing sector radically transformed the canned salmon industry between 1896 and 1915. On the harvesting side, the appearance of floating fish traps developed in 1902 were quickly adopted throughout the Gulf of Alaska regions (Colt 2000). The floating fish traps using nets to drive and capture salmon on their way to spawning streams were capital intensive structures owned and operated by the canneries. Further, they reduced labor needs in the harvesting sector. Their effectiveness was based on the general pattern of salmon to follow the shoreline on their migrations from the ocean back to their spawning streams. Floating fish traps required “toe holds” where they were anchored to the shoreline. In order to make this possible the Forest Service, that had become the primary landholder in southeast Alaska and Prince William Sound through the creation of National Forests in 1902 and 1907, established a program that allowed the canneries to obtain a lease on a small piece of waterfront property to which the floating trap could be attached. With the stimulation of demand for canned driven by World War I, floating fish traps proliferated and by the 1920s had emerged as the predominant harvesting technology capturing 50% or more of the annual harvest in most years. An overwhelming number of the traps were owned and operated by canneries headquartered in Seattle who transported their own labor and supplies to Alaska each spring to conduct their annual activities. There were no limits placed on the number of traps that could be constructed and by the mid-1920s over 800 were in use. Regulations established how far they must be from the mouths of streams, the distance between the traps, but neither the length nor the depth of the nets were regulated. Regulations initially allowed the traps to fish six days a week but enforcement was limited.

There were also major developments in mobile gear. In the mid-1910s, internal combustion engines were placed in fishing vessels making fishermen much more mobile. In addition, new vessel designs allowed purse seine gear to stored and deployed from the deck of the vessel. Throughout Alaska, boat builders created mostly smaller vessels in the 25-foot class that allowed fishermen to travel to numerous fishing sites and transport their harvests to tenders or directly to the canneries. Fishermen with such vessels were able to make their own decisions on where and when to fish and were independent of cannery tenders and transporters. By the mid-1920s, fishing boats using purse seines worked by a crew spread rapidly across salmon fisheries of the Gulf of Alaska. Washington fishermen with larger vessels over 50 feet in length also began coming to Alaska to fish due to larger Alaska runs and the declines in Washington salmon runs.

The major axis of conflict over control of the governance of Alaska salmon pitted the outside cannery owners with their fish traps against the resident mobile gear fishermen, small processors and Alaska business interests. The cannery owners wielded great influence in Washington DC through their lobbyists with both the politicians and the bureaucrats. Richard Cooley (1963) demonstrated how between the 1920s and 1950s the fisheries bureaucrats saw themselves as primarily responsible for facilitating the cannery owners’ enterprises. Alaska delegate to Congress Anthony Dimond in 1923 commented that the positioning and efficiency of the fish traps in harvesting salmon made “…it impossible for a fishermen using any other device to make a living.” In response to the limitations on their production capabilities and political influence, mobile gear fishermen began stealing fish from the traps or bribing trap watchmen to take a load. Annual reports of the Bureau of Fisheries in the 1920s and 1930s listed all of the fishermen arrested for fishing violations of this type, many of which involved trap thefts and most of whom are identifiable as Alaska Natives (Arnold 2008).

Another significant arena of conflict in salmon fisheries was between the work force – laborers and fishermen – and the canneries: capital and labor. The development of unions in other areas of the US economy stimulated unionization among cannery labor. The Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB), an organization created by the Tlingit in 1912 to pursue citizenship, also led the formation of a cannery workers union in the 1920s. Prior to the development of larger vessels with internal combustion engines, fishermen had mostly been employees of canneries. But with the emergence of fishermen with their own vessels, they too formed unions or associations with the intent of negotiating fish prices with the cannery owners. Fishermen’s organizations as unions were outlawed by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and upheld by court decisions that deemed them independent businesspersons, not laborers. New associations of fishermen sprung up that were able to undertake fish price negotiations but exercised no other bargaining rights. On a number of occasions in various regions of Alaska the associations have “sat on the beach” effectively striking for better prices.

Bristol Bay was a special case of Alaskan salmon fisheries due to the incredible size of the return, the short period in which the run occurred and the large amount of labor required to capture and process the salmon in a timely manner. There was a shortage of local Alaska Native labor in the region and so canneries imported fishermen and cannery workers to Bristol Bay by the thousands. Alaska Natives were shouldered aside and their traditional fisheries ignored. While smaller traps were initially tried in Bristol Bay, the shallow waters and huge pulses of fish made them difficult to work with. As a result, drift gillnetting from sail-powered ketches and set gillnets became the predominant harvesting methods. The canneries and fishermen’s unions kept Alaska Natives out of the sailboat drift gillnetting fishery limiting them to use of set nets that were largely for “personal use”, the term used in the federal period for traditional fisheries now termed “subsistence”.

Throughout this period, the canning industry operated primarily out of Seattle on a highly colonial basis with owners, most of the workforce, and fishermen migrating north each spring for the fishing season and returning in the fall with the salmon “pack” – the production of the years activities. As noted above, the early emergence of salmon information acquisition for governance was driven by the threat to salmon runs and the effort to save them. However, the situation in Bristol Bay displayed another interest in the development of data about salmon runs. For the canneries, each season was an enormous gamble in that funds had to be expended to provide all the materials necessary for canning the salmon and shipping them to Alaska before the fish appeared. Information on what to expect for the coming season would assist them in developing their plans and determining what scale of materials acquisition would fit with the expected return. Thus was born the impetus to the development of information and means to predict the runs of the coming season that would then inform decisions about how big a pack to expect and what quantities of materials to transport This was an extremely significant factor in the Bristol Bay region where huge runs returned in less than a month requiring mobilization of major investments in equipment and labor to process the fish.

Territorial Governance II: 1912 – 1959

In 1912, the federal government passed the Second Organic Act creating the Territory of Alaska including a Territorial Legislature (Haycox 2002). Members were elected from the four judicial districts. However the Governor was still appointed by the President and Congress maintained control over resources and most other matters. In 1918, the Alaska territorial legislature created the Alaska Territorial Fisheries Commission. The legislature nominated four individuals to serve on the board to the Governor who either could accept or reject them. Commission members were appointed based on their residence – one from each of the judicial districts – and the Governor served as chair (ATFC 1919). In its first report in 1919, the commission put forward positions several important themes that would continue in the discourse of Alaskans mostly until 1959 when Alaska became a state (ATFC 1919). The commission expressed the hope that Alaskans would be able to control their resources and that Alaskan residents would reap the benefits from the canned salmon fishery. Minutes from the commission indicate that the very small budget available to them was devoted to a hatchery, to stream clean-up activities, and development of recommendations to the Bureau of Fisheries concerning salmon fisheries regulations (ATFC 1919).

Examination of records associated with the Alaska Territorial Fisheries Commission show that political factors were central to its functioning (ATFC 1919-1928). Governor Bone commented that he would not accept one of the legislature’s proposed commissioners, despite his qualifications, due to the fact that he did not vote for the Governor’s legislation. In addition, Alaska Native leader, lawyer and legislator William Paul was a powerful voice for Alaskan Native and mobile gear fishermen who staunchly opposed fish traps and the cannery owners. In 1925, Commissioner J.R. Heckman recommended to Governor Bone that Paul replace him but the Governor rejected him stating Paul was a “troublemaker.” One type of troublemaking that Paul engaged in was to request copies of the minutes of the commission’s meetings. The governor replied that it was too expensive to send copies but Paul could come and read them in the Juneau office; Paul lived in Ketchikan. No records for the commission were found after 1928 although it appears to have existed until 1933.

The explosive wave of expansion in the number of canneries brought on by World War I and the demand for canned salmon led to a massive increase in salmon harvests. By the early 1920s, evidence of plummeting salmon runs, brought on in part by decline in demand, raised fears once again of the disappearance of salmon (Cooley 1963). The Ahtna experienced sharp reductions in salmon returning to the Copper River as their subsistence harvests plummeted from 43,970 in 1915 to 5,500 in 1918 pushing them to the edge of starvation (Simeone and Valentine 2007: 23). They informed federal fisheries agents of these catastrophic declines resulting from the establishment of an in river cannery at Abercrombie, 55 miles above the delta. Visits by the government agents confirmed their reports. These concerns, as well as those from other Alaskan voices, rose to the highest level of the federal government and was a crucial issue that President Harding took up during his visit to Alaska in 1924. Harding had appointed Herbert Hoover as Secretary of Commerce, the home of the Bureau of Fisheries and he was therefore the lead figure in assimilating information about Alaskan fisheries and advocating for new directions. In 1923, Hoover gave a pivotal and remarkably clear-eyed address on the status of Alaskan salmon and indicated his support for major changes that would restore reduced runs and move toward sustainable future. He took in testimony from hearings and letters. He expressed his view that capacity must be reduced to curtail harvests. He noted that reservations were an important device to be used and pointed out that the closing or reserving of the Yukon, Kuskokwim and Copper Rivers to commercial fisheries had accomplished increased runs that benefitted the Native people resident on the rivers. He stated that he would establish an Advisory Board of Alaskans to make recommendations and review policy. Harding also stated that “There is an obligation to the native Alaskan Indian, which conscience demands us to fulfill” in regard to their rights to lands and resources although his administration did not take any steps in this direction (Arnold 2008: 100).

In 1924, under Hoover’s leadership, Congress passed the White Act that substantially changed the governance of Alaska salmon fisheries. It placed complete control and administrative authority of Alaska salmon under the Bureau of Fisheries in the Department of Commerce (Gregory and Barnes 1939: 49). Its major conservation provision was the requirement that salmon be managed to insure the necessary escapement by allowing for 50% of the return to reach the spawning grounds. This requirement necessitated the systematic collection of data on salmon escapement leading to the Fish and Wildlife Service to request funding for such studies. Salmon weirs had first been used on the Karluk River in 1921 to determine how many salmon reached the spawning grounds. Some increase in funding for weirs and later stream surveys during spawning season was forthcoming but the massive data collection called for by the law largely went unmet (Cooley 1963). Federal managers utilized opinions of the field agents and stream guards as best estimates. Nevertheless, the legislation was considered a major factor in rejuvenating Alaska salmon runs that reached historic levels in the mid-1930s (Gregory and Barnes 1939: 55).

An important social provision of the act was its stipulation “no exclusive individual right to fisheries shall be granted” a repudiation of cannery operators desire to have property rights created for fish trap locations. The result was that the Bureau of Fisheries could control harvests by areas, seasons, and technological efficiency, but not by limiting units of gear. The legislation was strongly disapproved of by Alaska Natives and non-Native mobile gear fishermen as it neither outlawed nor imposed stricter regulations on the traps (Arnold 2008). In addition, it also statutorily limited the taking of fish for “personal use, not for sale or barter” to hand rod, spear and gaff, thereby outlawing weirs and traps. It should be noted that Alaska Natives were generally exempt from such fish laws and regulation and enforcement of personal use laws were inconsistently enforced until the 1950s (Simeon and McCall 2007: 23). However, Ahtna leader Katie John stated that at her family’s fishing site on Tanada Creek (Batzulnetas), her father had used a weir and traps every year until the 1940s when a federal game warden came to Batzulnetas and told her father that he was no longer to use fish traps at their site (Simeone and McCall 2007: 45). After that experience, her father never returned to Batzulnetas with his family to obtain the special fish on which they had depended for generations.

During the 1930s, another significant development occurred as fleets of fishing vessels from Japan appeared in Bristol Bay where they legally harvested salmon outside the three mile limit that defined the US territorial sea. Japanese fishing began in 1930 and continued for the next five years (Gregory and Barnes 1939: 303). The US government sent a statement to the Japanese government in 1937 stating that their offshore fishing was a cause of “distinct concern” as US policies of restraint on its own salmon fisheries may be compromised by Japanese fishing. As a matter of policy the US statement stipulated that there was a “superior interest and claim to the salmon resources of Alaska” and “the fact that salmon taken from waters off the Alaskan coast are spawned and hatched in American inland waters, and when intercepted are returning to American waters, adds … to the conviction that there is in these resources a special and unmistakable American interest” (Barnes and Gregory 1939: 305). While the Bristol Bay fishery was the immediate focus of US concern, the US statement noted that should such efforts appear elsewhere off the shores of Alaska, they would also be similarly regarded.

In the 1940s, the issue of Alaska Natives and the salmon fishery emerged again in the context of a major shift in federal policy under President Roosevelt to politically recognize and economically support Indian tribes. A centerpiece of the new approach was the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. Harold Ickes as Secretary of the Interior used the provisions of the IRA, supported by the opinion of Solicitor Nathan Margold in 1941, to create the fishery regulations to establish Alaska Native reservations that would include their fishing grounds (Case and Voluck 2012). Using the provisions of the 1936 Alaska Indian Reorganization Act (AIRA), Secretary Ickes established the Karluk Fisheries Reserve in 1943, consisting of land and waters up to 3,000 feet offshore, for the benefit of the Karluk native population who had essentially been denied commercial access to their traditional salmon resource. Court decisions in the late 1940s limited the control over who could fish in the waters of the Karluk reserve and placed the burden of enforcement on the local tribe instead of federal agents. This effectively compromised the purpose of the reserve (Case and Voluck 2012). In southeast Alaska, Ickes invited tribes to submit claims for reservations and hearings were held in three villages on their claims. The establishment in 1949 of the Hydaburg reservation – passed by the Haida residents by a vote of 81 – 3 was overturned in 1951 (Case and Voluck 2012: 106). Kake and Klawock voted down the reservation proposed for them due, among other things, to the inadequacy of the lands and waters included. The policy to establish reservations for Alaska Natives as means to resolve aboriginal rights issues was essentially dead by 1952.

During World War II salmon harvests increased to accommodate, national war needs. World War II stimulated a substantial increase in the Alaska population because of the massive buildup of military installations across the territory. After the war, the number of non-Native fishermen in southeast Alaska shot up from about 1500 in 1946 to over 4500 in 1952 (Arnold 2008: 134). Following the war, stronger interest in Alaska becoming a state grew certainly fueled by the desire for jobs in the salmon fishing industry. One of the central interests of supporters was gaining control over resources, especially the salmon fisheries, and directing the benefits of the commercial salmon fishery to Alaskan residents by outlawing fish traps. In 1947, an advisory vote taken on the legality of fish traps found that Alaska residents opposed them by 7 to 1. To that end in 1949, the Alaska legislature created the Alaska Territorial Fishery Service with a charge to explore and develop Alaska’s views on fisheries and make recommendations to the Fish and Wildlife Service on proposed regulations and other matters. In 1951, a sport fishing section was added to the fishery service. In 1957, a further development of this expression of a desire for local control of resources was the establishment of the Alaska Fish and Game Commission. There was significant debate about the membership of this body in particular about whether specific sectoral interests should be represented. The legislature preferred a board composed of three commercial fishermen, one processor, one sport fisherman, one trapper and one at large to insure there would be informed parties to deliberate on issues that would be come before the board. A five-member board without sectoral composition was also under discussion. The Alaska Sportsmen Association, an organization whose membership included many influential Alaskans, submitted a recommendation to the Alaska legislature shortly after Statehood proposing a governing structure consisting of persons “knowledgeable” about the resources, appointed by the Governor, and confirmed by the legislature.

In the early 1950s, salmon harvests and returns continued their downward slide begun in the 1940s from the abundant returns of the 1930s. Total salmon harvest in 1953 reached an historic low and the Fish and Wildlife Service proposed reductions of 50% in traps for 1954. Fisheries managers expressed concern over the enormous increase in the number of fishermen particularly in Bristol Bay, Cook Inlet and southeast Alaska.

In late 1953, FWS Director Donald McKernan called a meeting with the major processors in Juneau to discuss the seriousness of the decline and discuss proposals for the coming year. Minutes from the meeting show that the processing magnates rebuffed proposals for cutting fishing time and harvests in half. Some contended that their experience in the 1920s showed that poor runs could be followed by abundant returns. One suggested that an earlier year of low returns was the result of over escapement in the previous cycle. A number voiced the view that salmon declines were the result of poor weather and environmental conditions not overharvesting so that fishing decisions should be made more based on environment and less based on return or escapement. The idea for an advisory committee of Alaskans on salmon fisheries was advanced again by Donald McKernan, FWS director of Alaskan fisheries in 1955. In a letter to Director McKernan in 1955, M. Sarvela of the North Pacific Fishery Vessels Owners Association remarked, “It is the first time we have ever been given such consideration by your office.”

Another dilemma for users and managers of salmon in addition to low returns was the reappearance in 1952 of Japanese salmon harvesting fleets in Bristol Bay outside of the three-mile limit (Finley 2011: 40). Japanese fishing was in fact supported by the federal government as a means to assist the Japanese in rebuilding their economy. Both Alaskans and non-Alaskans expressed outrage and began a political process to halt the offshore fisheries. In 1954, North Pacific Fisheries Act, in response to the International Convention for the High Seas Fisheries of the North Pacific Ocean signed by representatives of the US, Canada and Japan authorized creation of the North Pacific Fisheries Commission (NPFMC). Based on commission research based on tagging salmon caught in offshore waters and determining their spawning areas, it was determined that Alaska salmon ranged far out into the Bering Sea during the oceanic phase. Fishing for salmon east of 175˚ W (Atka Island) was banned. However, no enforcement of the ban was implemented.

One of the important governance changes in the early 1950s to address the problem of the enormous increase in harvesting capacity was the movement to area licensing. This policy was to require fishermen to be licensed to only one of Alaska’s designated management areas for salmon fishing during a season. This was seen as a way for resident fishermen in the area to obtain a greater share of the fisheries near their home and eliminate the ability of the larger vessels to focus on the peak of the runs in many areas. Prior to this, it was possible and indeed common for the larger, more mobile purse seine vessels – many of which came from Puget Sound – to begin fishing across the Gulf of Alaska beginning at Unimak Island in the Aleutian region, then sequentially fishing in Chignik, Kodiak, Cook Inlet, Southeast and finally ending their season with fall fishing in Puget Sound. The establishment of area licensing in 1954 halted this pattern of “high grading” by fishing areas when the run was at its peak.

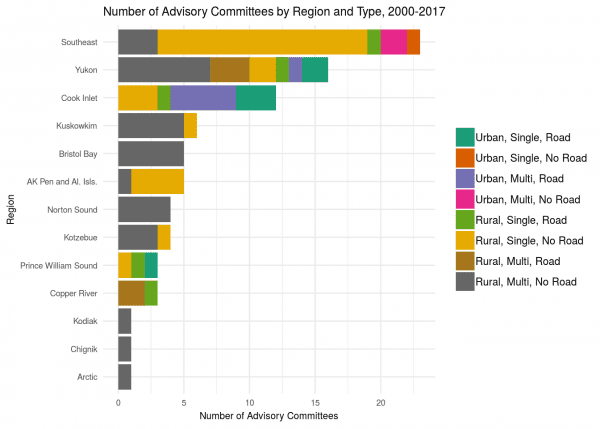

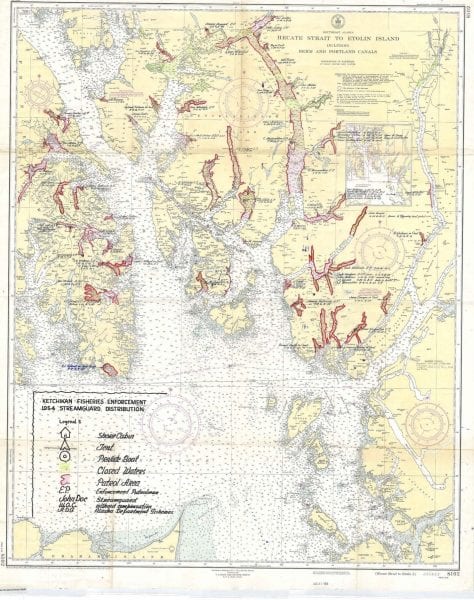

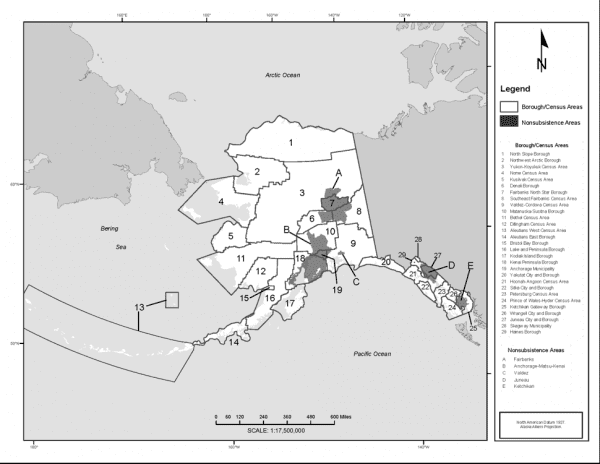

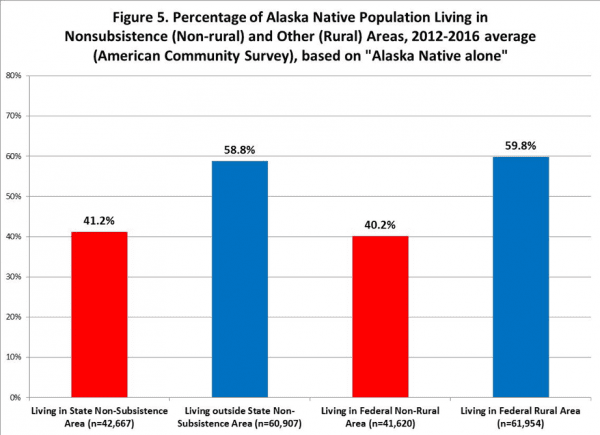

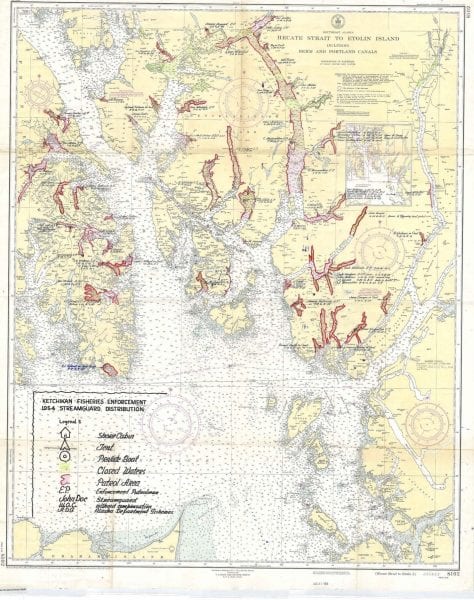

A quick look at the practices of federal salmon management in Alaska in the early 1950s is revealing. The Fish and Wildlife Service headquarters were in Washington, DC. Alaska, the region was divided into eleven areas each of which had at a minimum an area biologist, staff, support personnel and a warden. In December in preparation upcoming year after reviewing the area reports, regulations for the coming season were prepared based on historical information about catch and, if available escapement. They were circulated for written comments and review by staff. After revision, they were sent to the processors and fishing population in February and hearings were held in a few locations – Seattle, Juneau – after which final regulations for the year were issued. In a few cases, area biologists traveled to outlying communities and held meetings with fishermen on the proposed regulations. These meetings were mostly informational as there was little opportunity for the fishermen to effect the regulations. The organization then turned to in-season management. The figure below shows how the region around Ketchikan was managed in 1954. Regulations define waters that were closed (yellow hatched areas). Stream guards were located at various campsites and equipped with skiffs to patrol their assigned areas (red outlined zones) watching for violations of closed waters and seasons. The map shows the dates the stream guards were in the field. There were also larger vessels that traveled throughout the region depending on needs for coverage. Some of the stream guards were paid by the territory and some by the Fish and Wildlife Service. Stream guards submitted annual reports as did the area warden on the citations for the season to the area manager who incorporated them into his annual area report to the director (FWS 1955).

Figure 1. Ketchikan Fisheries Enforcement – 1954 Source: National Archives, USFWS files, Seattle, Washington

As the push for Alaskan statehood gained steam, the Territorial Legislature convened a special convention in 1955 to draft a state constitution. In his opening address to the convention, former Governor Gruening (1967) stated:

“It is colonialism that has both disregarded the interest of the Alaskan people and caused the failure of the prescribed federal conservation function. Colonialism has preferred to conserve the power and perquisites of a distant bureaucracy and the control and special privileges – the fish traps – of a politically potent absentee industry.”

In keeping with this sentiment, paramount in the considerations of the convention delegates was the establishment of the fisheries as common property of citizens of Alaska, that no right to the fisheries be established, management of resources for “sustained yield” and development of resources of Alaska to benefit its people. Statehood was opposed by the salmon cannery industry, as it was clear that Alaska’s citizenry would move quickly to outlaw fish traps. While statehood had substantial support among Alaskans, it was by no means universal. Alaska Natives were skeptical as they watched Alaska’s statehood proponents draft and submit legislation that would create the state without recognizing or disclaiming Alaska Native rights (Metcalfe 2014). In 1956, the territorial legislature conducted a vote on the proposed constitution along with an advisory vote on the status of the hated floating fish traps. The Constitution passed by a 2 to 1 margin and the abolishment of fish traps passed by a 5 to 1 margin. Despite considerable discussion at the Constitutional Convention in 1955, no mention of Alaska Native rights is found in the Constitution of the State of Alaska. In 1957, the Territorial Legislature created the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG) supplanting the former Alaska Territorial Fisheries Service.

The new agency was charged to prepare for a complete takeover of fish and game management when statehood was achieved. Clarence Anderson, who had served in the Alaska Territorial Fishery Service, was appointed as the first Commissioner of the ADFG (Clark et al 2006). Early in his tenure, Anderson laid out some of policies that he intended to implement. A number of the ideas had been discussed for many years. He envisioned much greater flexibility in management by giving authority to open and close fisheries to area managers. As part of increasing flexibility, he suggested shortening the notification period to 6 hours as it was three days in federal management. He proposed that citizen input to the Board of Fish and Game should be solicited through advisory committees that would be set up in communities to review proposals and submit their own. In-season decision-making was to be based on escapement data and this would require a major upgrade in the scientific and technical capacities of the department.