Alaska Department of Fish and Game. 2017. Estimated Harvests of Fish, Wildlife, and Wild Plant Resources by Alaska Region and Census Area, 2014. Division of Subsistence. http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/static-sub/CSIS/PDFs/Estimated%20Harvests%20by%20Region%20and%20Census%20Area.pdf

Apgar-Kurtz, Breena. 2015. Factors affecting local permit ownership in Bristol Bay. Mar Policy 56: 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.02.013.

Carothers, C., & Chambers, C. (2012). Fisheries privatization and the remaking of fishery systems. Environment and Society: Advances in Research, 3(1), 39-59.

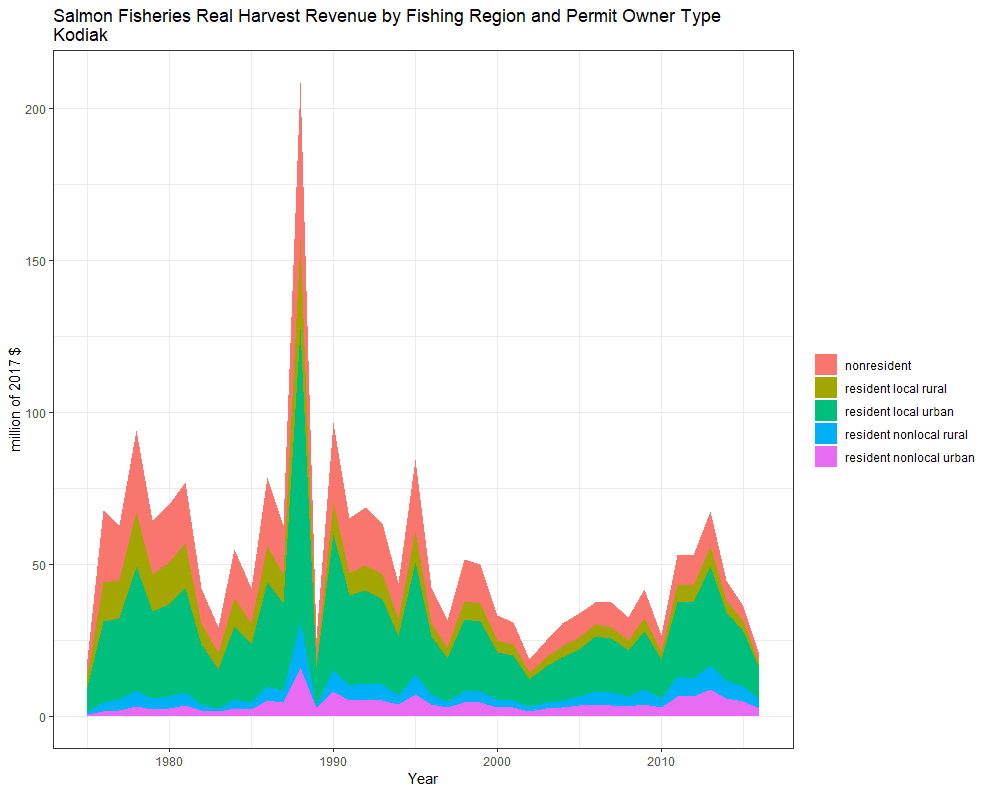

Carothers, Courtney. 2008. Rationalized out: Discourses and realities of fisheries privatization in Kodiak, Alaska. In Enclosing the fisheries: People, places and power. American Fisheries Society Symposium.

Coleman, J. , C. Carothers , R. Donkersloot, D. Ringer, P. Cullenberg, A. Bateman. 2018. Alaska’s Next Generation of Potential Fishermen: A survey of youth attitudes towards fishing and community in Bristol Bay and the Kodiak Archipelago, Alaska. 2018. Maritime Studies.

Commercial Fisheries Entry Commission (CFEC). (2015). Executive summary-changes in the distribution of Alaska’s commercial fisheries entry permits, 1975-2014 (CFEC Report No. 15-03N EXEC). Juneau, AK.

Crowell, A., Steffian, A., & Pullar, G. (2001). Looking both ways: Heritage and identity of the Alutiiq people. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press.

Cullenberg, R. Donkersloot, C. Carothers, J. Coleman, D. Ringer. Turning the Tide: How can Alaska address the ‘graying of the fleet’ and loss of rural fisheries access? A review of programs and policies to address access challenges Alaska fisheries. Report funded by the North Pacific Research Board and Alaska Sea Grant, 2017. Available at: fishermen.alaska.edu.

Donkersloot, R. and C. Carothers. 2016. Sustaining the next generation of fishermen and fishing communities: Understanding fisheries access in coastal Alaska. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development.

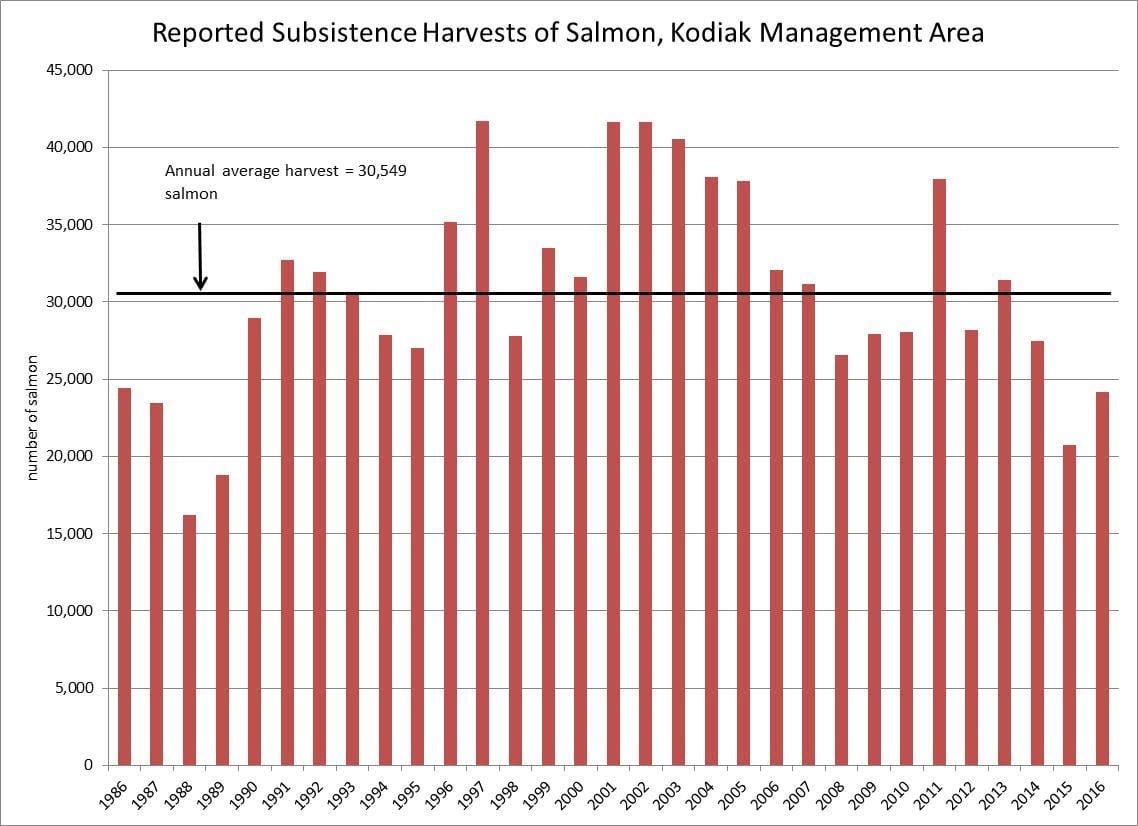

Fall, James A, Anna Godduhn, Gabriela Halas et al. 2018. Alaska Subsistence and Personal Use Salmon Fisheries 2015 Annual Report. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence Technical Paper No. 440. Anchorage.

Fitzhugh, B. (2003). The evolution of complex hunter-gatherers: Archaeological evidence from the North Pacific. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic-Plenum Publishers.

Gho, M. & C. Farrington, 2018. Changes in the distribution of Alaska’s commercial fisheries entry permits, 1975-2017 (CFEC Report 18-2N). Retrieved from: https://www.cfec.state.ak.us/RESEARCH/18-2N/18-2N.html

Himes-Cornell, A., Hoelting, K., Maguire, C, Munger-Little, L, Lee, J., Fisk, J., … Geller, C. (2013). Community profiles for the North Pacific Fisheries. U.S. Department of Commerce. NOAA Technical Memo NMFS-AFSC-259: 210. Retrieved from https://www.afsc.noaa.gov/Publications/AFSC-TM/NOAA-TM-AFSC-259/VOLUME%205.pdf

Knecht, R. (1995). The late prehistory of the Alutiiq people: Culture change on the Kodiak archipelago from 1200-1750 AD (Doctoral dissertation). Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, PA.

Langdon, Steve J. 1980. Transfer patterns in Alaskan limited entry fisheries: Final report for the limited entry study group of the Alaska State Legislature.

Marchioni, Meredith, James A. Fall, Brian Davis, and Garrett Zimpleman. 2016. Kodiak City, Larsen Bay, and Old Harbor: An Ethnographic Study of Traditional Subsistence Salmon Harvests and Uses. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence Technical Paper No. 418. Anchorage.

Mason, R. (1993). Fishing and drinking in Kodiak, AK: The sporadic re-creation of an endangered lifestyle (Doctoral dissertation). University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

Mason, R. (1995). The Alutiiq ethnographic bibliography. Kodiak, AK: Kodiak Area Native Association.

McDowell Group. (2016). Economic impact of the seafood industry on the Kodiak Island borough. Prepared for the Kodiak Island Borough & City of Kodiak. Anchorage, AK.

Mishler, Craig. 2003. Black Ducks and Salmon Bellies: An Ethnography of Old Harbor and Ouzinkie, Alaska. Occasional Paper Series Volume Two, The Alutiiq Museum and Archaeological Repository. Virginia Beach, VA: The Donning Company Publishers.

National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries Service. (2015). Report on holdings of individual fishing quota (IFQ) by residents of selected Gulf of Alaska fishing communities 1995-2014. November 2015. Retrieved from https://alaskafisheries.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/reports/ifq_community_holdings_95-14.pdf.

Pullar, G. (2009). Historical ethnography of nineteenth-century Kodiak villages. In Haakanson Jr., S., & Steffian, A. (Eds.), Giinaquq Like a Face: Sugpiaq Masks of the Kodiak Archipelago (pp. 41-60). Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press.

Reedy-Maschner, Katherine L. 2007. The best-laid plans: Limited entry permits and limited entry systems in eastern Aleut culture. Hum Organ 66 (2): 210–225. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.66.2.97231040w8jt857n.

Ringer, D., C. Carothers , R. Donkersloot, J. Coleman, and P. Cullenberg. 2018. For generations to come? The privatization paradigm and shifting social baselines in Kodiak, Alaska’s commercial fisheries. Marine Policy, 98: 97-103.

Ringer, D. 2016. For generations to come: Exploring local fisheries access and community viability in the Kodiak Archipelago. M.A. Thesis, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK.

Roppel, P. (1986). Salmon from Kodiak: A history of the salmon fishery of Kodiak Island, Alaska. Anchorage, AK: Alaska Historical Commission.

Steffian, A., Saltonstall, P., & Kopperl, B. (2006). Expanding the Kachemak: Surplus production and the development of multi-season storage in Alaska’s Kodiak archipelago. Arctic Anthropology, 43(2), 93-129.

Williams, Liz, Philippa Coiley-Kenner, and David Koster. 2010. Subsistence Harvests and Uses of Salmon, Trout, and Char in Akhiok, Larsen Bay, Old Harbor, Ouzinkie, and Port Lions, Alaska, 2004 and 2005. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence Technical Paper No. 329. Anchorage.