Observing declines in salmon size

Salmon Size Decline Map: Select a species, then hover over a region to see trends in body size of salmon.

Salmon Size Decline Map: Select a species, then hover over a region to see trends in body size of salmon.

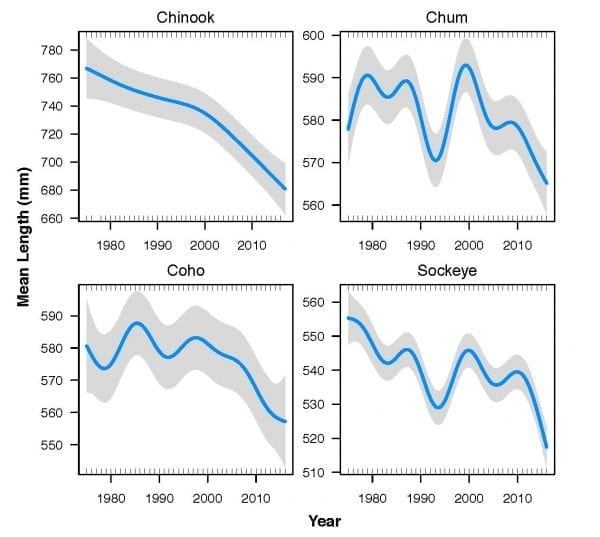

Plots were created using over 7.5 million data points of measured fish collected by Alaska Department of Fish & Game and partners such as US. Fish & Wildlife Service, National Park Service, tribal entities, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada. The data represent fish in commercial catch and escapement projects, using a general additive model on size change through time.

Across Alaska, salmon are returning from sea at younger ages with smaller adult body sizes. Alaskans have long noted these changes, as have previous scientific studies. Until now, no project has compared trends across all of Alaska’s regions and species.

By analyzing patterns of body size among salmon species from across the state, we are learning more about how and why salmon are getting smaller. The goal is to eventually understand the causes and consequences of those changes. We find that Chinook (also known as king), coho (silver), chum (dog), and sockeye (red) salmon are all getting smaller. Patterns of change vary among species, regions, and even rivers.

It is clear that in general, Alaska salmon are getting smaller and the declines are most stark for Chinook salmon. These changes are especially pronounced in the past 15-20 years. Unfortunately, although they are the most abundant species in Alaska, very few data on pink salmon are available. So, we cannot address whether pink salmon are changing in size through time.

Salmon populations can become smaller bodied, on average, in two non-mutually exclusive ways. First, they may be growing smaller if they cannot acquire enough food at sea. This results in salmon of the same age that are smaller than they were in the past. Second, salmon may return from the ocean at younger ages. Because salmon continue to grow as they age, older salmon are generally larger than younger salmon.

In Alaska, all four species of salmon are getting smaller primarily because they are returning from the ocean at younger ages.

Research has found that no single factor can explain changes in salmon size. Instead, salmon face many factors that collectively contribute to smaller size and younger age, including a warming climate, increased predation from marine mammals, fisheries-induced evolution (or changes in the characteristics of salmon due to fishing gear that preferentially catches large, old salmon), and increased competition from highly abundant wild and hatchery salmon at sea.

Smaller salmon have important consequences for Alaska’s people, economy, and ecosystems. For subsistence users, smaller salmon mean fewer calories and grams of protein per fish. If subsistence users cannot catch more fish in years when fish are small, they will have fewer meals of salmon.

Smaller salmon are also a problem for commercial fisheries, which may lose profits because smaller fish have less meat and cannot be processed into high value products.

Alaska’s rivers, lakes, and forests rely on salmon nutrients. Smaller salmon could mean bears, eagles, trout, and other species that eat salmon or their eggs will receive less food. Less of the important nutrients that salmon bring with them from the ocean will enter freshwater and forest food webs. Smaller salmon also lay fewer eggs, imperiling salmon populations by possibly reducing the number of salmon born in each subsequent generation.

Image credit: Andrew Hendry

Learn how a small “army” of data scientists collected and organized vast amounts of data on Alaska’s salmon – and why this matters. A Search and Rescue Team for Salmon Data

How A Massive Dataset and A Set of Rural Communities Are Helping to Sustain Alaska’s Salmon. Podcast: Alaska’s Exceptional Salmon Data