Ahtna leader Wilson Justin stands at the memorial to Katie John erected at Batzulnetas, the fish camp at which she fought for the right to continue customary and traditional salmon fishing. Credit: Steve J. Langdon

When US Army explorer Lt. Henry Allen arrived at the headwaters of the Copper River in 1885, he found the local people engaged in harvesting and processing salmon to use for the winter food as they had been for centuries. He named one of these meeting places Batzulnetas – an Anglicization of the name for the leader of the local group. For Ahtna, salmon were a foundational food source with whom they had a special relationship in order to insure the return of salmon in the future.

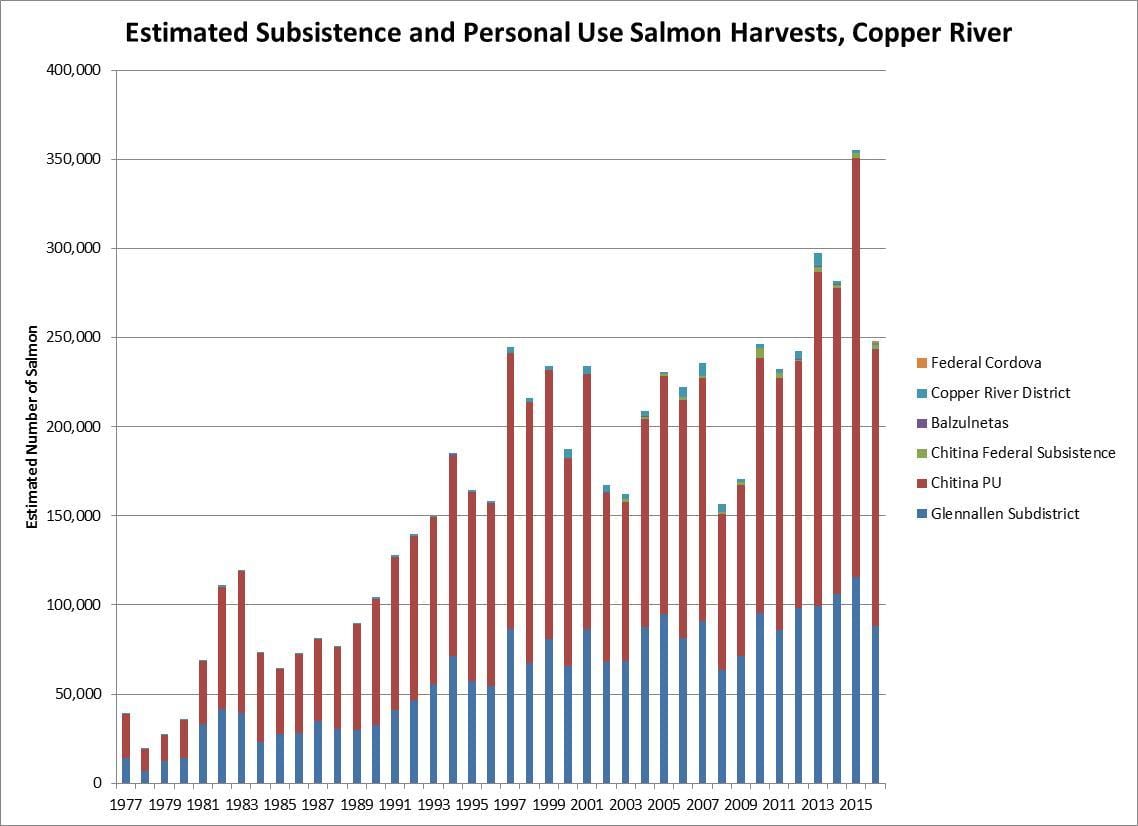

Recent research has documented the extensive traditional knowledge about salmon held by the Ahtna and the difficulties the Ahtna have faced in maintaining their relationship with salmon following the coming of Americans (Simeone and Kari 2002, Simeone and McCall 2007, Simeone 2014, Simeone 2018). The first experience of impact came immediately following the establishment of a cannery on the Copper River below Chitina in 1915. Ahtna observed that their harvests were sharply declining and they complained to federal agents that salmon populations were being damaged. They asked the agents to have the cannery removed. Investigations by federal agents found that Ahtna subsistence harvests had fallen form nearly 44,000 fish in 1915 to 5,500 in 1918 (Simeone and McCall 2007:23).

Fisheries agents began implementing regulations on the commercial fishery in 1918 but runs did not recover and in 1921 commercial salmon fishing in the Copper River was prohibited. Commercial fishing was allowed to continue at the mouth of the river and subsequent years provided evidence that the commercial fishery seriously cut into Ahtna subsistence harvests and spawning escapements.

During these years, Ahtna used fish wheels for most of their harvests with dip nets and rod and reel also contributing. Ahtna were the overwhelming majority of salmon harvesters on the Copper River after the passage of the White Act in 1924, whose purpose was to regulate harvests to insure escapement until 1960 when the state of Alaska took over fishery management from the federal government (Simone and McCall 2007).

At Batzulnetas, traditional weirs and traps were banned by federal marshals in the 1940s. Katie John, a young woman at the time, had fished there and knew it as her family’s ancestral fishing site and loved it. However, her family had to move from their customary and traditional site and so began fishing at Mentasta about 20 miles away where they continued their salmon fishing. In 1960 the newly created State of Alaska took over salmon management and in 1964 closed down the subsistence fishery at Batzulnetas and all other traditional salmon fishing sites in the upper Copper River. Despite the closure, Batzulnetas endured in the minds of the Upper Ahtna as a special place.

In 1971, under the terms of the Alaska Native Land Claims Settlement (ANCSA), aboriginal fishing and hunting rights of Alaska Natives were “extinguished” but with the proviso that Alaska Native subsistence needs were to be taken care of by state and federal policies. The State did not act to protect and provide for Alaska Native subsistence needs although a state law stating that subsistence was to be the priority for harvests when shortages occurred was passed in 1978. Nevertheless, the State continued the ban on subsistence harvests in the upper Copper River.

In 1981 the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) was passed placing much of Alaska land and waters in federal jurisdictions. Title 8 of the act provided a rural resident subsistence preference, distinguishing Alaska Native from non Native bases. The priority was to be activated when resource strength could not accommodate users other than rural residents. State regulatory authority on federal lands was tied to the implementation of a similar policy for state resource allocation. In the early years after the passage of ANILCA, in 1984, Katie John and Doris Charles submitted a proposal requesting the Alaska Board of Fish to allow them to subsistence salmon fish at Batzulnetas. Their request was denied despite the fact that hundreds of thousands of salmon were being taken for commercial and sport purposes in the ocean and on the river below them.

In 1985, Katie John and two other elders filed suit to force the Board of Fisheries to open their fishery and won their case. In response, the State Board of Fish provided a limited, highly restrictive and inadequate opening. Katie John returned to court and the state opening was struck down as too restrictive. Before the State Board of Fish could respond, the state supreme court held in the McDowell (1989) case that a rural (or place-based) preference was unconstitutional under the state constitution.

When the Alaska legislature chose not to pursue a constitutional change, the federal Secretaries of Interior and Agriculture began the process of providing for the ANILCA rural preference on federal lands. Initially, the federal government provided the same limited opening that had been determined to be inadequate in 1985. Katie John, using Native American Rights Fund (NARF) lawyers, petitioned for reconsideration of the regulation to which the federal agencies responded that Tanada Creek and the upper Copper River were navigable waters and that such waters were not considered “public lands” and therefore not subject to Title 8 jurisdiction.

Native American Rights Fund (NARF) lawyers, representing Katie John and other plaintiffs, filed suit stating that this construction of navigable waters was in error in that Section 102 of ANILCA states “the term ‘lands’ means land, waters, and interests therein…” In 1991, the question of whether navigable waters were included as part of public lands was litigated and it was determined by the Ninth Circuit of Appeals that the federal government indeed had an “interest” in “reserved water rights.” Further legal questions were also addressed in subsequent cases bringing about decisions over ownership of waters, submerged lands, and state compliance with federal law.

In March 1994 the case was argued with the previously opposed federal government now joining with Katie John concerning the federal “interest” in “navigable waters.” Less than a month later, the court concluded that the federal government, not the state, had the authority to regulate the taking of fish on “navigable waters” in “public lands” stipulating that the US government “holds title to an interest in navigable waters in Alaska.” The decision was appealed to the Ninth Circuit court that determined in April,1995 that subsistence priority applies to inland navigable waters in which the United States has reserved water rights. Federal agencies then went on to determine which waters were included in that definition. These determinations in 1999 extended federal jurisdiction over inland “navigable waters” in or adjacent to federal conservation units, not including the general public domain lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management.

While the State and other interested parties explored the possibility of appealing the ruling to the Supreme Court, the Governor of Alaska decided not to pursue it. This decision paved the way for Katie John and the Upper Ahtna to be authorized by the Federal Subsistence Board (FSB) to return to Tanada Creek and engage in salmon harvesting and preservation at their “customary and traditional location.”