Commercial Fisheries Entry Commission (CFEC) 2017. Data request: permanent permit holdings in Alaskan communities for limited salmon fisheries.

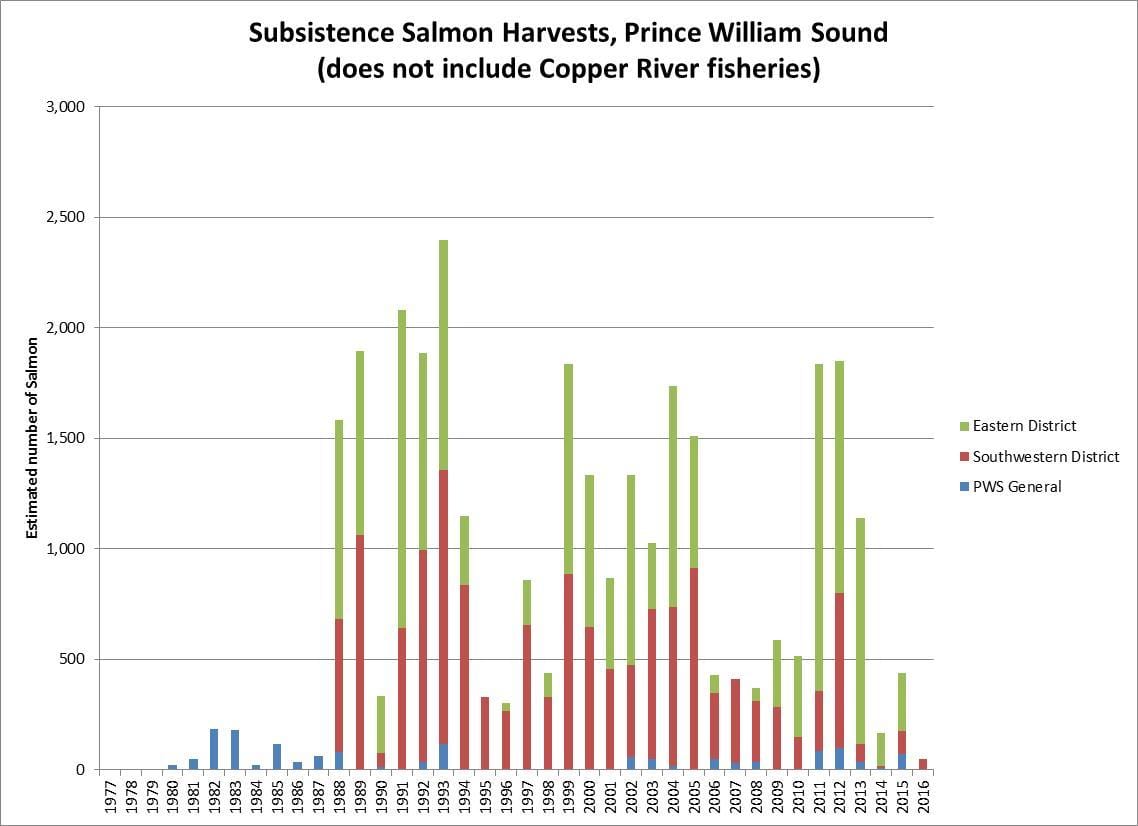

Fall, James A. Lee Stratton, Philippa Coiley, Louis Brown, Charles J. Utermohle, and Gretchen Jennings. 1996. Subsistence Harvests and Uses in Chenega Bay and Tatitlek in the Year following the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence Technical Paper No. 199. Juneau.

Fall, James A. et al. 2018. Alaska subsistence and personal use salmon fisheries 2015 annual report. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence Technical Paper No. 440. Anchorage.

Fall, James A., Rita Miraglia, William Simeone, Charles J. Utermohle, and Robert J. Wolfe. 2001. Long-Term Consequences of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill for Coastal Communities of Southcentral Alaska. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence Technical Paper No. 264. Anchorage.

Field, L. Jay, James A. Fall, Thomas S. Nighswander, Nancy Peacock, and Usha Varanasi, editors. 1999. Evaluating and communicating subsistence Seafood Safety in a Cross-Cultural Context: Lessons Learned from the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill. Pensacola, FL: Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC).

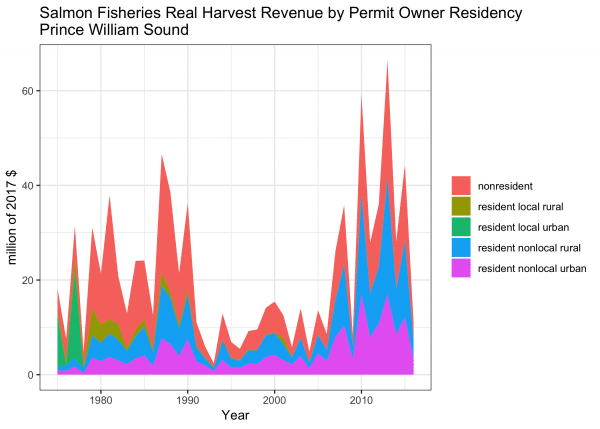

Gho, M. (2014b). CFEC Permit Holdings and Estimates of Gross Earnings in the Prince William Sound Salmon Fisheries, 1975-2013. Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Gho, M. and Farrington, C. 2017. Changes in the distribution of Alaska’s commercial fisheries entry permits, 1975-2016. Juneau, Alaska: Commercial Fisheries Entry Commission.

Gill, D. A., Ritchie, L. A., & Picou, J. S. (2016). Sociocultural and psychosocial impacts of the Exxon Valdez oil spill: Twenty-four years of research in Cordova, Alaska. The Extractive Industries and Society, 3(4), 1105–1116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2016.09.004

Himes-Cornell, A., K. Hoelting, C. Maguire, L. Munger-Little, J. Lee, J. Fisk, R. Felthoven, C. Geller, and P. 2013. Community profiles for North Pacific fisheries – Alaska. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA Tech. Memo. NMFS-AFSC-259, Volume 1, 70 p.

Holen, D. (2014). Fishing for community and culture: the value of fisheries in rural Alaska. Polar Record, 50(255), 403–413. https://doi.org/10/f6jrs5

Holen, D., Fall, J. A., & La Vine, R. (2011). Customary and Traditional Use Worksheet: Salmon, Copper River District, Prince William Sound Management Area (Special Publication No. BOF 2011-06) (p. 46). Anchorage, Alaska: Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Lang, D. W. (2010). A Survey of Sport Fish Use on the Copper River Delta, Alaska (General Technical Report No. PNW-GTR-814) (p. 56). Portland, Oregon: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. Retrieved from http://andrewsforest.oregonstate.edu/pubs/pdf/pub4513.pdf

Miraglia, R. A. (2012). Did I Hear That Right? One Anthropologist’s Reaction to Colleague’s Testimony in a Court Case Involving Alaska Native Aboriginal Hunting and Fishing Rights on the Outer Continental Shelf. Indigenous Policy Journal, 22(4). Retrieved from http://articles.indigenouspolicy.org/index.php/ipj/article/view/49