Alaska Department of Fish and Game. 2017. Estimated Harvests of Fish, Wildlife, and Wild Plant Resources by Alaska Region and Census Area, 2014. Division of Subsistence. http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/static-sub/CSIS/PDFs/Estimated%20Harvests%20by%20Region%20and%20Census%20Area.pdf

Anderson, T. J., Russell, C. W., & Foster, M. B. (2013b). Chignik Management Area Salmon Annual Management Report, 2013 (Fisheries Management Report No. 13-43) (p. 94). Anchorage, Alaska: Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Dumond, D.E. 1977. The Eskimos and Aleuts. London. Thames and Hudson.

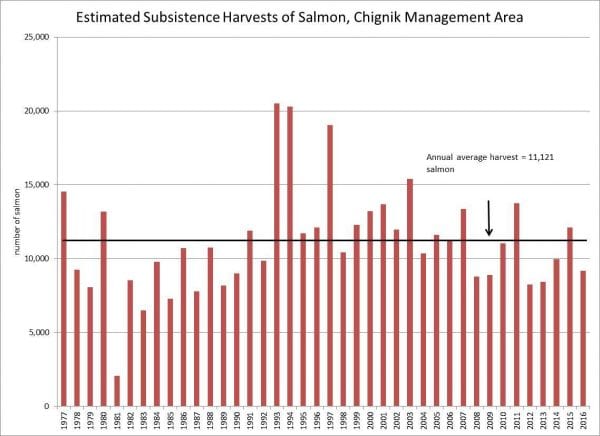

Fall, James A. et al. 2018. Alaska Subsistence and Personal use Salmon Fisheries 2015 Annual Report. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence Technical Paper No. 440. Anchorage.

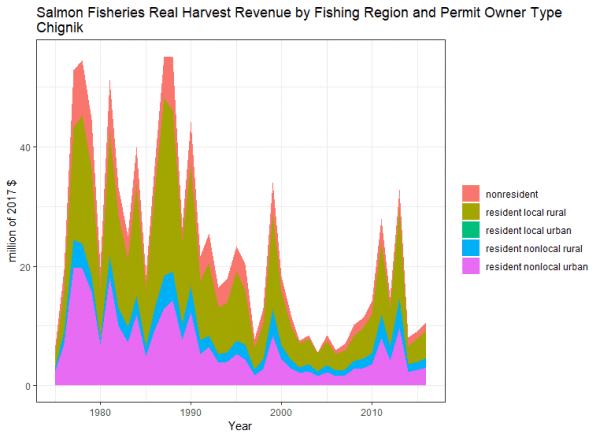

Gho, M. (2016). CFEC Permit Holdings and Estimates of Gross Earnings in the Chignik and Alaska Peninsula Commercial Salmon Fisheries, 1975- 2014. Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Griffiths, J. R. & Schindler, D. E. Consequences of changing climate and geomorphology for bioenergetics of juvenile sockeye salmon in a shallow Alaskan lake: Changing climate and geomorphology affect juvenile sockeye salmon bioenergetics. Ecology of Freshwater Fish 21, 349–362 (2012).

Haycox, S. 2002. Alaska: An American Colony. University of Washington Press, Seattle.

Henn, W. 1978. Archaeology of the Alaska Peninsula: The Ugashik Drainage, 1973-1975. University of Oregon Anthropological Papers, 14, Eugene.

Hutchinson-Scarbrough, L., Marchioni, M. A., & Lemons, T. (2016). Chignik Bay, Chignik Lagoon, Chignik Lake, and Perryville: an Ethnographic Study of Traditional Subsistence Salmon Harvests and Uses (Technical Paper No. 390) (p. 260). Anchorage, Alaska: Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Hutchinson-Scarbrough, Lisa and James A. Fall. 1996. An Overview of Subsistence Salmon and Other Subsistence Fisheries of the Chignik Management Area, Alaska Peninsula, Southwest Alaska. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence Technical Paper No. 230. Juneau.

Knapp, G. (2004). Selected Economic Effects of the Chignik Salmon Co-operative. Remarks prepared for the Alaska Board of Fish.

Knapp, G. (2007). The Chignik salmon cooperative: a case study of allocation to a voluntary self-governance organization. Anchorage, Alaska: University of Alaska, Anchorage. Retrieved:http://www.iser.uaa.alaska.edu/people/knapp/personal/pubs/Knapp_Chignik_Salmon_Coop–Case_Study_of_Allocation_to_a_Voluntary_Self_Governance_Organization.pdf

Morris, Judith M. 1987. Fish and Wildlife Uses in Six Alaska Peninsula Communities: Egegik, Chignik, Chignik Lagoon, Chignik Lake, Perryville, and Ivanof Bay. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence Technical Paper No. 151. Juneau.

Partnow, P.H. 2001. Making History: Alutiiq/Sugpiaq Life on the Alaska Peninsula. University of Alaska Press, Fairbanks.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2011. Profiles of general demographic characteristics, Alaska: 2010. U.S. Department of Commerce, Washington, D.C.

Walsworth, T. E., Schindler, D. E., Griffiths, J. R. & Zimmerman, C. E. 2015. Diverse juvenile life-history behaviours contribute to the spawning stock of an anadromous fish population. Ecology of Freshwater Fish 24, 204–213.

Westley, P. A. H., Schindler, D. E., Quinn, T. P., Ruggerone, G. T. & Hilborn, R. Natural habitat change, commercial fishing, climate, and dispersal interact to restructure an Alaskan fish metacommunity. Oecologia 163, 471–484 (2010).